48

LNG

INDUSTRY

OCTOBER

2016

Superficially, amine treating is simple. On the surface,

there are absorption and regeneration columns, with

solvent circulating between them in a closed loop through

a few pieces of heat transfer equipment, including a cross

exchanger and trim cooler, with a reboiler and overhead

condenser serving the stripper. However, beneath the

surface, the chemistry is complex. The system is reactive;

absorption and regeneration produce and consume large

amounts of heat; the solvent is a high strength ionic

solution, making the thermodynamics not ideal; and the

gas phase is often at extreme pressures of more than

100 bar. Modern treating frequently uses a solvent with

more than a single amine, which is almost always the case

in LNG production. It is extremely difficult to design such

facilities reliably without a clear understanding of the

physics and chemistry of the system as embodied, for

example, in a rigorous mass transfer rate-based simulator.

Given the high economic cost of the CO

2

removal section

of an LNG plant, it is surprising that antiquated simulators

are still used for design when the modern mass transfer

rate-based approach is commercially available. Using

dated tools results in needless design risk and a lack of

reliability, which can cause plants to only reach a fraction

of their nameplate capacity, or use oversized equipment.

Falling short

There are numerous reasons that LNG plants fail to meet

design throughput, either at start-up or after some time in

operation. The focus here is on the CO

2

removal section of

the LNG plant, and on some of the factors that can cause

design shortfalls and operating problems that limit plant

capacity. Apart from using an inadequate simulator and

unknowingly generating designs that are too tight, these

may include inadequate attention to the following in the

design phase:

Solvent contaminants, such as heat stable salts,

hydrate inhibitors (e.g. glycols, methanol), and amine

degradation products.

Changing blend composition because of disparate

amine volatilities.

Liquid and vapour distribution in towers.

Sensitivity to variation in parameters, such as changing

gas and liquid composition and coolant temperatures,

all of which can be determined by adequate sensitivity

studies.

Due to the presence of high concentrations of acid

gases (and to some extent degradation products), amine

systems are highly corrosive. This can lead to the

following:

Corroded or missing trays and corroded packing.

Leaking heat exchangers.

Plugged instrumentation and equipment from corrosion

products.

On the operations side, plants rarely run at steady

state. In attempting to win a construction bid, if a

contractor has developed a tight design without solid

knowledge of how tower internals actually perform from a

mass transfer (vs hydraulic) standpoint, normal process

fluctuations can throw a plant in and out of compliance

with meeting gas treating objectives. This list is by no

means exhaustive, but it does contain the majority of the

common causes for performance shortfalls. These will be

discussed individually in this article.

Tight designs

The expectation that the separation or gas purity

achievable by a given volume of packing should depend

on the packing type and size ought to be no surprise.

Therefore, gas treating process simulators should have a

rigorous way to account for the particulars of the tower

internals on the separation. Unfortunately, the designer

does not have this information and, as such, should

not be relied upon to provide this knowledge. It is easy

to calculate the number of ideal stages for a specified

separation, but it is difficult to take the results of the

calculation into an actual volume of specific packing. This

has been discussed in detail in a paper presented at the

2016 Laurence Reid Gas Conditioning Conference,

1

where

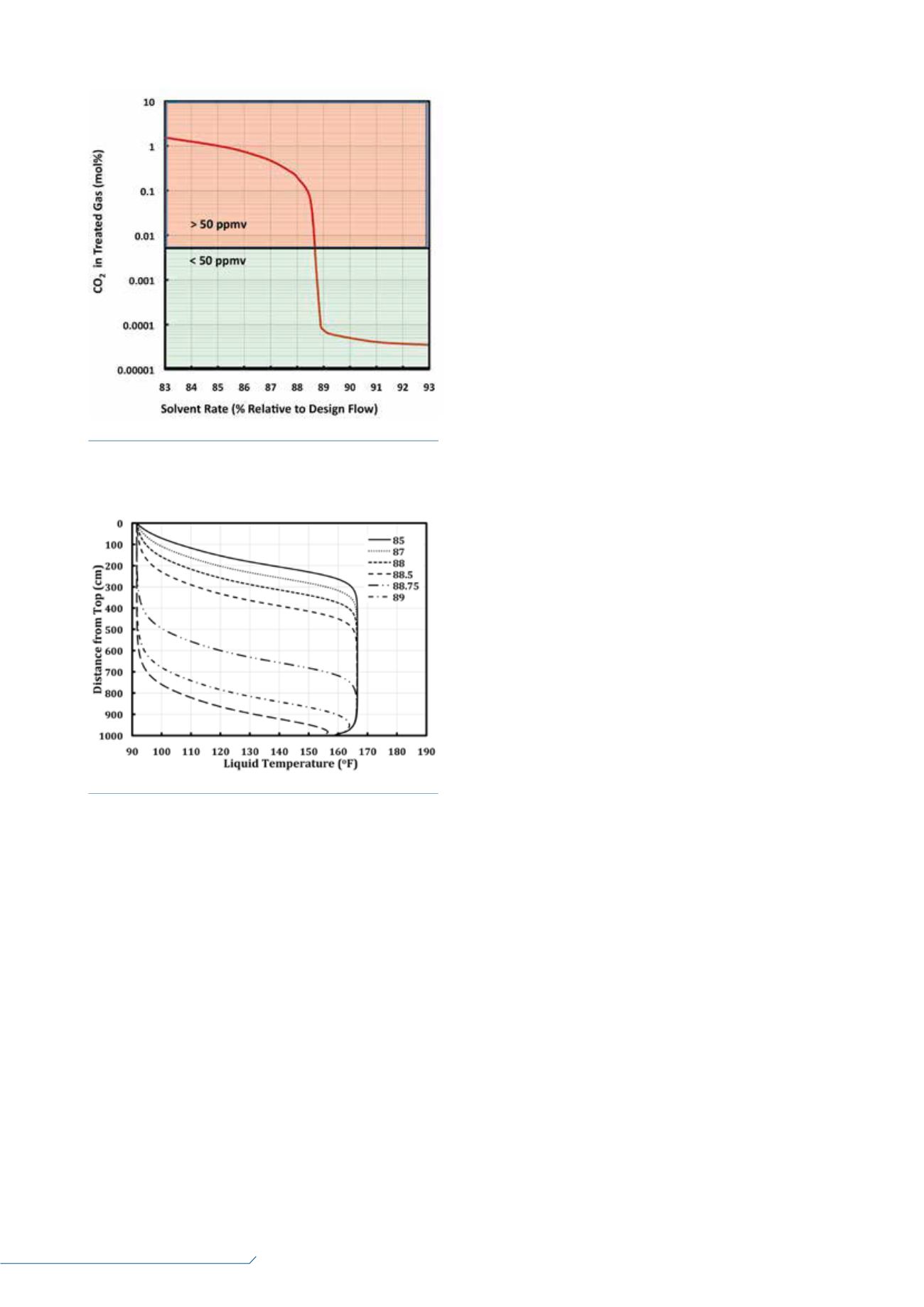

Figure 1.

CO

2

leak from a piperazine-methyldiethanolamine

(MDEA) absorber.

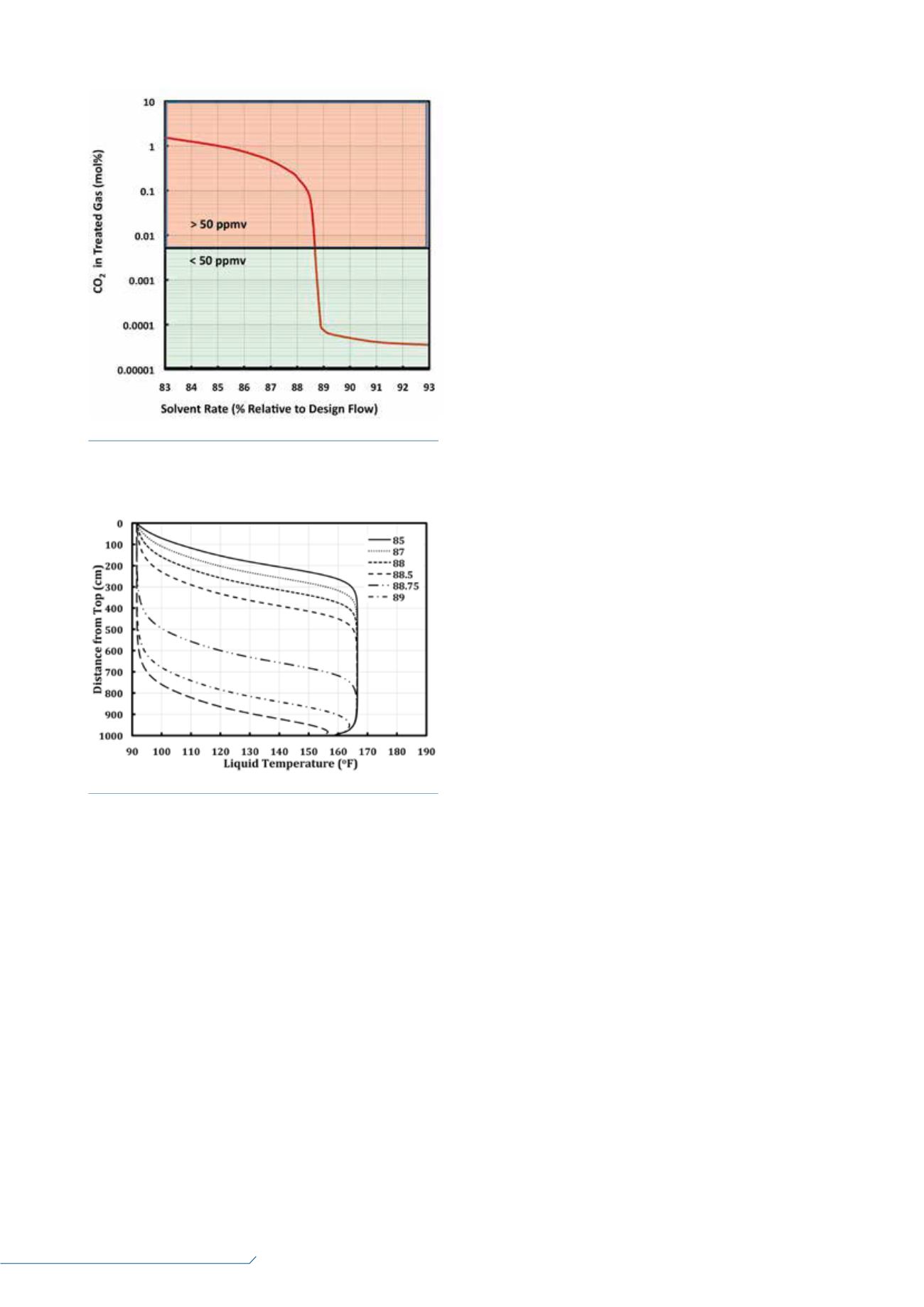

Figure 2.

Piperazine activated MDEA absorber temperature

profiles.