50

LNG

INDUSTRY

OCTOBER

2016

the base of columns, particularly packed columns of large

diameter, as well as trayed columns. Failure to do so can

cause serious maldistribution of gas (and, consequently,

liquid) over the column’s cross section, which will lead to

poor treating performance.

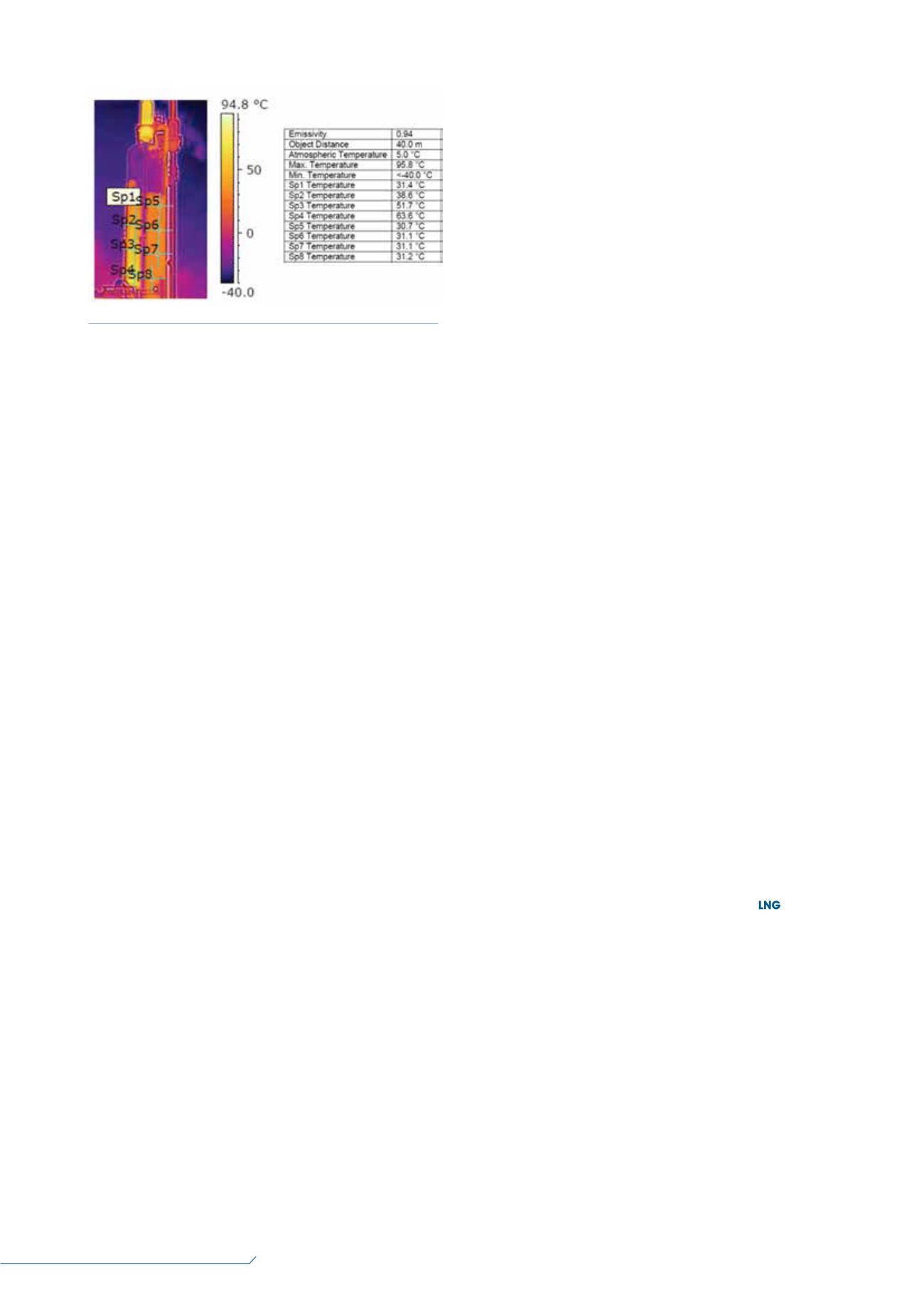

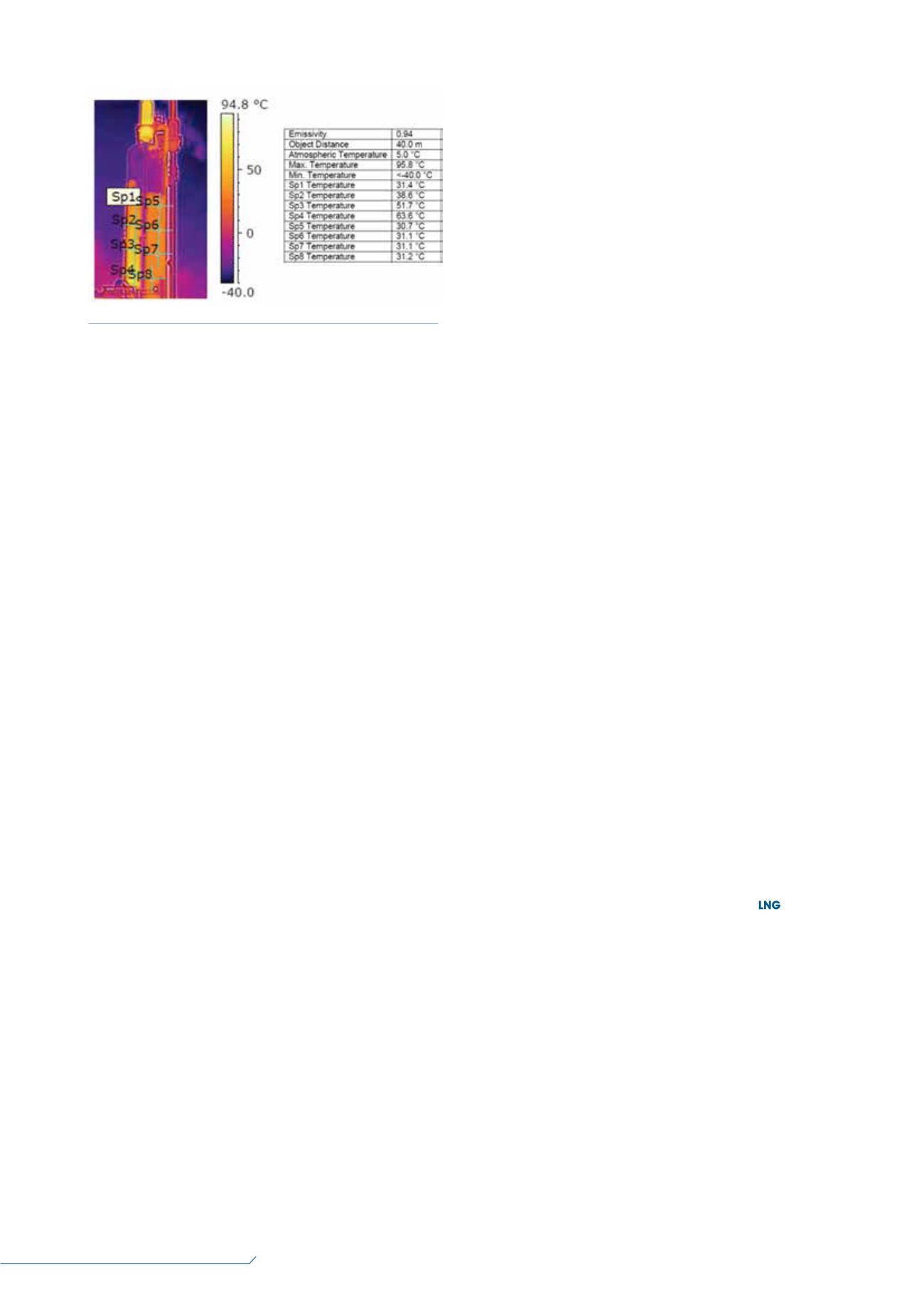

A useful pair of tools for assessing maldistribution,

whether gas, liquid, or both, is mass transfer rate-based

simulation and thermal imaging of the tower. Figure 3

shows a thermal image of the upper two-thirds of an

absorber in an ammonia plant using a piperazine-promoted

MDEA-based solvent (the lower third could not be imaged

from this position because of the proximity of other

equipment). The position of the gas inlet nozzle was behind

the column as it is seen in the photograph and towards its

left side. As the table in Figure 3 shows, the temperature

profile along the height of the absorber exhibited a distinct

bulge along its left side (above the gas inlet nozzle) near

the bottom of the image, but an almost uniform

temperature (and equal to the lean solvent temperature)

on the wall opposite the nozzle. This column was suffering

from poor gas distribution. It is certainly not normal to see

great temperature asymmetries around the periphery of a

correctly operating column. Instead of trying to match the

plant measured treating performance by tuning an obtuse

parameter, such as tray efficiency or residence time per

theoretical stage, a true mass transfer rate model would

reveal that the wetted interfacial area would need to be

derated.

Corrosion

Missing and corroded trays can be hard to diagnose

without expensive gamma scans. However, if tray damage

is suspected, a thermal scan may show anomalies in

longitudinal temperature distribution, especially when

compared with mass transfer rate-based simulation.

Because a mass transfer rate model uses actual trays, not

idealisations, and assumes that all trays are operating

properly, simulation of a column with fewer operating trays

than it is supposed to contain may allow the simulation

to reproduce tower performance data. Similarly, reducing

the effective interfacial area in the packed bed will allow

the simulation to reproduce performance data if packing is

missing or badly damaged. Comparison with thermal scans

may also provide further evidence of packing or tray damage.

On the other hand, moderate foaming can actually

cause better performance than expected because of the

increased interfacial area consequent to the presence of

foam. Severe foaming, however, always degrades tower

performance. If a mass transfer rate-based simulation

needs 20% or 30% more area than physically provided by

the packing as simulated, foaming may be indicated.

A leaking heat exchanger, especially a cross exchanger,

can result in treating being missed by a wide margin if the

leak is from the rich side to the lean side of the exchanger

(as it most often is). Treating is usually fairly sensitive to

lean solvent loading of acid gas. The simplest diagnosis is

rate-based simulation of the regenerator, followed by a

comparative measurement of the solvent lean loading as it

enters the absorber and, if possible, upstream of the

exchanger as well. It should be noted, however, that lean

solvents can be hard to assess properly because H

2

S tends

to oxidise to thiosulfate in the presence of air. Again,

simulation will reveal whether the measured lean loading

is capable of satisfactorily treating the raw gas. In one

instance, mass transfer rate-based simulation pointed an

operator to resample around a lean/rich exchanger with

bottles pre-purged with nitrogen. The leak was confirmed

through sampling only after taking these and other

precautions to eliminate oxygen contamination.

Amine units can also fall short because of

instrumentation malfunctions caused by equipment fouled

not just by corrosion products, but also by materials

injected into the system for various reasons. Examples of

injected foreign materials include corrosion inhibitors,

antifoams, and oxygen scavengers. These materials

degrade and form gels and assorted sticky substances that

can plug level and flow meter pressure taps, resulting in

false readings. Suspended particulates erode orifice plates

and also lead to false readings.

Conclusion

The CO

2

absorbers in LNG plants (and other deep CO

2

removal applications, such as syngas) can fail to meet

expectations for a wide variety of reasons. The most

common ones have been discussed in ths article. The

overriding lesson is that genuine mass transfer rate-based

simulation, coupled (where appropriate) with thermal

imaging, is an excellent tool not just for design, but for

troubleshooting and plant monitoring as well.

References

1. WEILAND, R., SCHULTES, M., PILLING, M.,

PORTILLO, J., SUMMERS, D., SHIVELER, G.,

DUSS, M., STEWART, E., and PRADERIO, A.,

‘Sensitivity of Treating Plant Performance to Tower

Internals’, paper presented at the Laurance Reid Gas

Conditioning Conference, Norman, Oklahoma, US,

(21

–

24 February 2016).

2. WEILAND, R. H., and HATCHER, N. A.,

‘Foundations of Failure’,

Hydrocarbon Engineering

,

(December, 2011), pp. 57 – 59.

3. SIEDER, G., KATZ, T., and HEARN, J., ‘How Glycols

Affect the Acid Gas Removal Process’, PTQ, Q4, (2013).

4. COOPER, E., and WEILAND, R., ‘Reducing CO

2

Slip from the Syngas Unit of an Ammonia Plant’,

paper presented at Nitrogen + Syngas 2016, Berlin,

Germany, (29 February – 3 March 2016).

Figure 3.

Thermal image of a CO

2

absorber.