14

LNG

INDUSTRY

APRIL

2016

companies to submit dozens of applications to US energy

regulators for permission to export LNG and build

liquefaction terminals. The issue now, however, is not that

the domestic supplies of natural gas are not there for

export, but that the global gas market has been turned on

its head since the gas export frenzy began. Global prices

for natural gas have collapsed due to the drop in the oil

price and weakened gas consumption growth in key

gas-importing markets.

Expectations of lucrative arbitrage opportunities

(especially in Asia) for North American LNG exporters have

been dashed for the time being. The outlook for global

LNG is now bearish, in marked contrast to the bullish

expectations of 2011 – 2013. Nevertheless, an LNG cargo

has now been exported and, by 2020, the US will be one of

the major global LNG exporters, alongside Qatar and

Australia. The difference is that, due to the current tough

market conditions, US LNG projects that have already been

sanctioned may take longer to produce to capacity, while

the rate of further project sanctioning will stall in the nearer

term.

To export or not to export

The US shale gas production boom that began around

2009 – 2010 generated a hotly contested debate about

the future of the US gas market. Large, domestic users

of natural gas, such as the petrochemical industry and

utilities, cautioned against prioritising the export of the

US’ shale gas bounty in the form of LNG out of fear that it

would lead to steeply rising domestic gas prices. However,

the oil and gas industry urged the Obama administration

not to stand in the way of the development of a US LNG

for export sector, as it represented a unique opportunity

not just for the US to become a major energy exporter, but

also for the country to become an influential player on how

the global gas market operates.

Global gas exports (both pipeline and LNG) are

dominated by a few suppliers, such as Russia and Qatar,

who mainly utilise oil-indexed pricing and long-term

contracts when selling gas to consumers. Furthermore, the

North American, European and Asian gas markets are quite

distinct, meaning that the gas trade is not quite as fungible

compared to how the global oil trade operates, with its

multiple sellers and buyers all over the globe. Significant

volumes of US LNG entering the market would not only

provide competitive pressure on existing exporters, which

would benefit large gas-importing economies in Europe

and Asia, but contribute to making regional gas markets

more inter-connected and liquid.

Project sanctioning begins in

earnest

The debate on whether the US should export LNG has

largely moved on, with the US Department of Energy

(DOE) granting approval for several companies to export

LNG to countries that do not have Free Trade Agreements

(FTAs) with the US. As of February 2016, there were 16

such approvals given by the DOE, with a further 30 under

review, for a total of 47.2 billion ft

3

/d in the regulatory

pipeline. However, the volume of LNG that will end up

being exported from the US is unlikely to be near this

level, as it exceeds the total amount of global LNG

exported in 2015. In addition to receiving export approval,

energy companies must also receive approval from the

US Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to

construct liquefaction facilities. This is done after a rigorous

inter-agency process, involving environmental and safety

reviews, as well as public consultation.

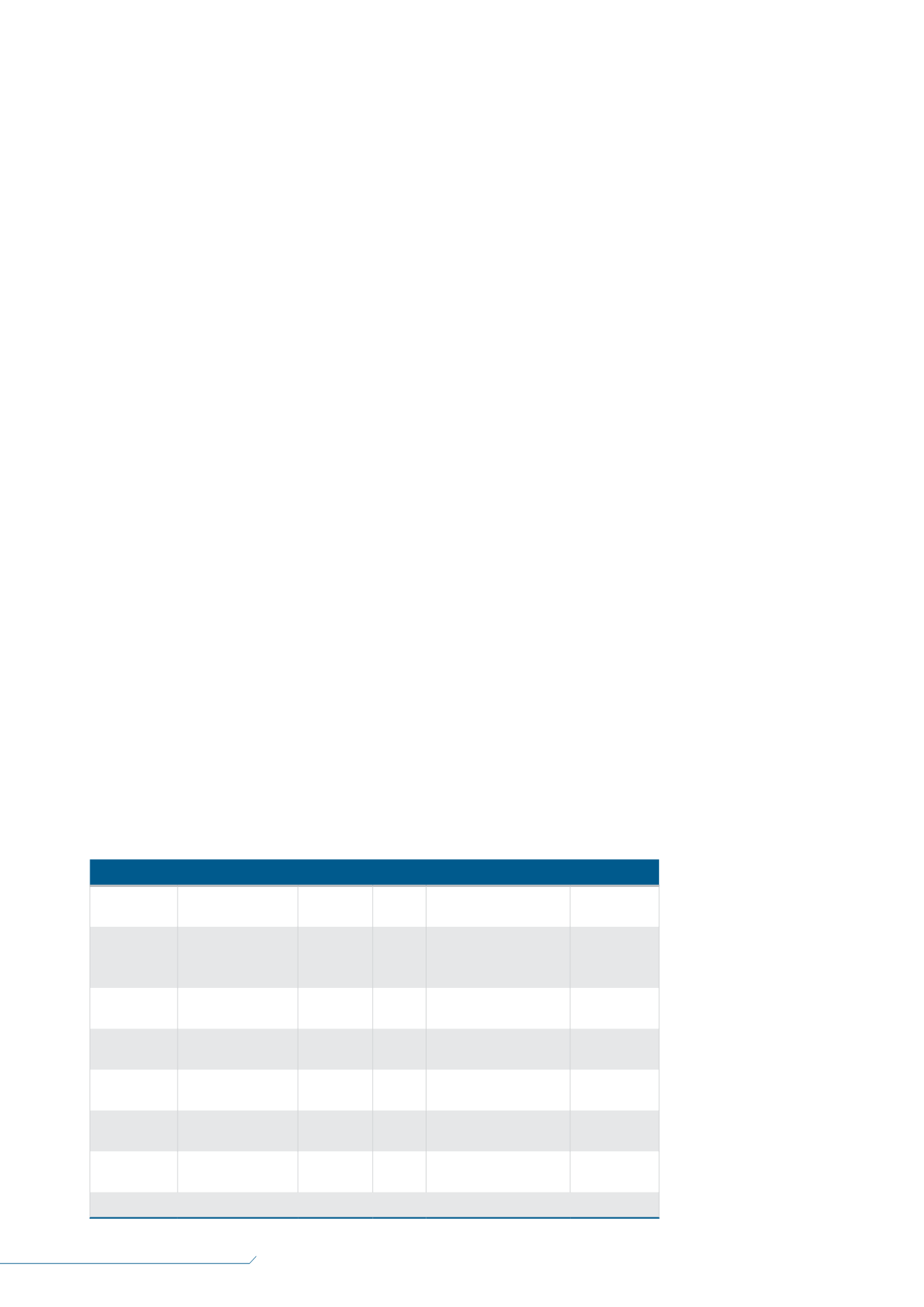

As of January 2016, FERC had approved six such

liquefaction projects (see Table 1). Of these, one has begun

operation, four have been sanctioned and are under

construction, and one has been sanctioned, but is not yet

being built. Nearly 83 million tpy in liquefaction capacity

has been approved, of which all should have begun

construction by 2019. This would put the US ahead of

Qatar (currently the leading LNG exporter) in terms of

liquefaction capacity, as the Gulf state has a capacity of

approximately 77 million tpy. By the end of this decade,

Australia will have approximately 85 million tpy in

liquefaction capacity, with five projects having come online

since 2012 and a further

three currently under

construction. By 2020,

therefore, the three

largest LNG exporters

will be Australia, the US

and Qatar. According to

FERC, a further 20 US

LNG export projects are

also awaiting regulatory

approval, but, given the

current market

conditions, it is unlikely

that most of these

projects will go ahead

even if they are

approved. Nonetheless,

the amount of LNG

capacity already

sanctioned is already

significant.

Table 1.

US LNG terminals approved by FERC

Terminal

Operator

Capacity

(million tpy)

Trains Status

Estimated first

Train start date

Sabine Pass

(Louisiana)

Cheniere/Sabine Pass

LNG

27

6

Operating (Train 1), under

construction (Trains 2 – 5),

not under construction

(Train 6)

February 2016

Cove Point

(Maryland)

Dominion – Cove

Point LNG

5.2

1

Under construction

June 2017

Hackberry

(Louisiana)

Sempra – Cameron

LNG

12

3

Under construction

March 2018

Freeport

(Texas)

Freeport LNG

13.2

3

Under construction

October 2018

Corpus Christi

(Texas)

Cheniere – Corpus

Christi LNG

9

2

Under construction

October 2018

Lake Charles

(Louisiana)

Southern Union –

Lake Charles LNG

16.45

3

Approved/not under

construction

2Q19

Sources: Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), World Gas Intelligence