62

LNG

INDUSTRY

OCTOBER

2016

pipes were rapidly doused in water, allowing the material

to fix the austenitic microstructure and obtain the required

set of mechanical properties. After descaling, the pipes

were straightened, pickled, cut to the required lengths, and

bevelled, as required for further welding.

The second step saw the mother pipes supplied from

the company’s hot formed shop, and reduced in ‘cold’

conditions to the required final size, either in one step or

in a number of intermediate steps, by means of pilgering

mills. After each of the cold forming steps, the tubes were

annealed in gas furnaces with temperatures of at least

1070°C and then pickled and passivated. Alternatively, the

tubes were bright annealed in a continuous hydrogen

furnace (Figure 2), allowing enhanced quality of the

surfaces. After the final forming, the tubes underwent

straightening, cutting to the required lengths, surface

finishing, and bevelling.

Quality of the production was checked in accordance

with the agreed test plan, which normally included visual

inspection and dimensional control, mechanical testing

for strength and robustness, flattening tests, ultrasonic

and eddy-current examination, and hydrotesting in order

to ensure structural integrity. Austenitic steels were

tested for resistance to intergranular corrosion, as in the

case of FLNG, according to Practice E of the ASTM A262

standard. Also, the material for sour environments was

checked against the requirement of the NACE 0175 and

ISO 15156 standards to decrease the risk of stress

corrosion cracking.

Materials control

Work on high quality production always begins with the

selection of raw materials. Strictly following requirements

for chemical composition within the limits given by the

reference standard is not typically enough. By controlling

the relative content of the alloying elements, it is possible

to limit the amount of ferrite in the austenitic matrix to

a narrow range, minimising instability in impact strength

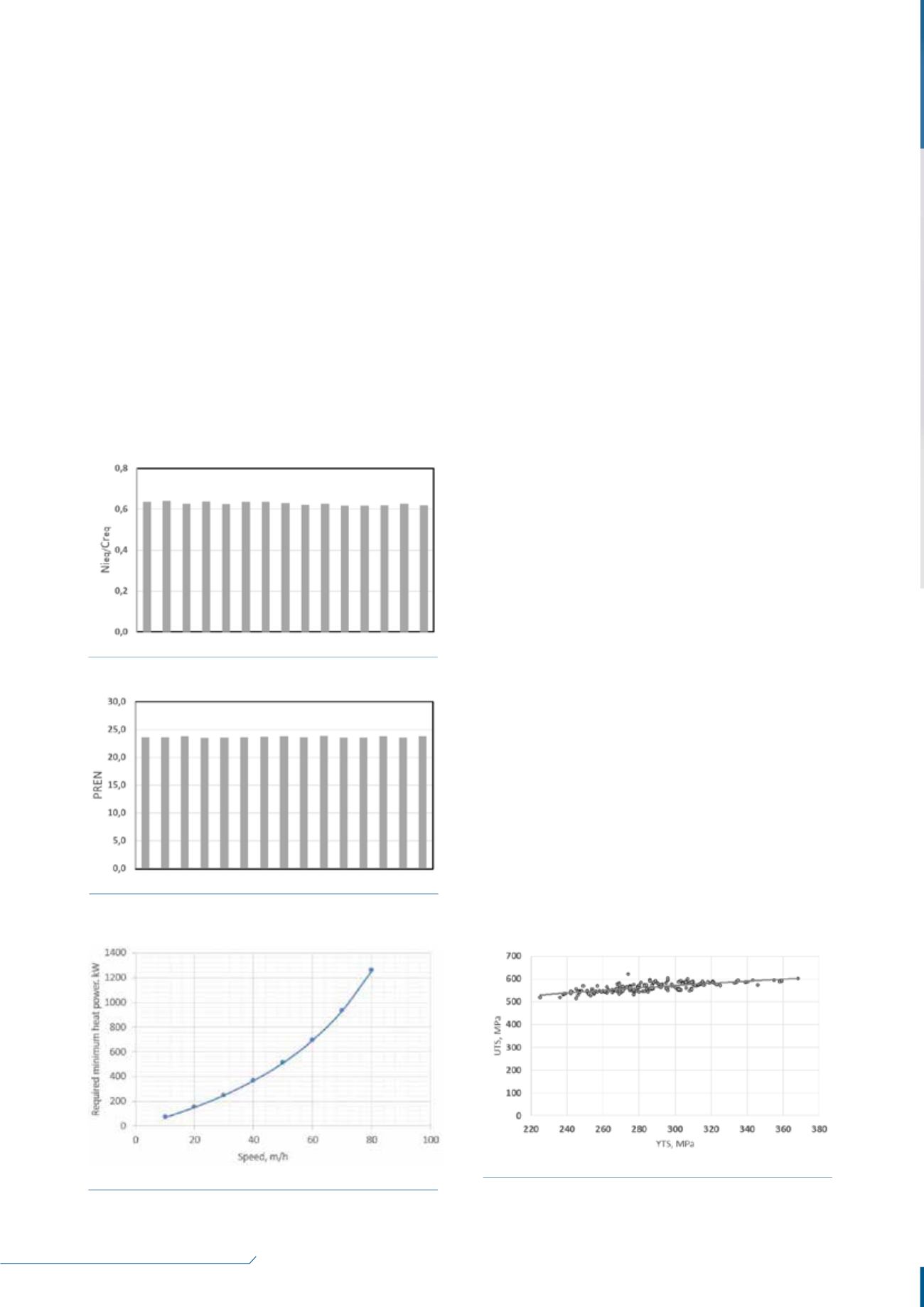

and corrosion properties. Figure 3 shows that the ratio of

Ni and Cr equivalents for the production heats was kept at

an average level of 0.63, with the variation not exceeding

1.5%. Another aspect of this exercise is in minimising the

variation of PREN. Figure 4 shows that the average PREN

was 23.7 and deviations were below 2%.

Heat treatment processes

Careful selection of heat treatment regimens is crucial for

the formation of the correct microstructure throughout

the entire wall thickness of the tube, allowing for the

necessary corrosion resistance and mechanical strength.

To achieve this, the material should be given the right

combination of heat input and soaking time for any heat

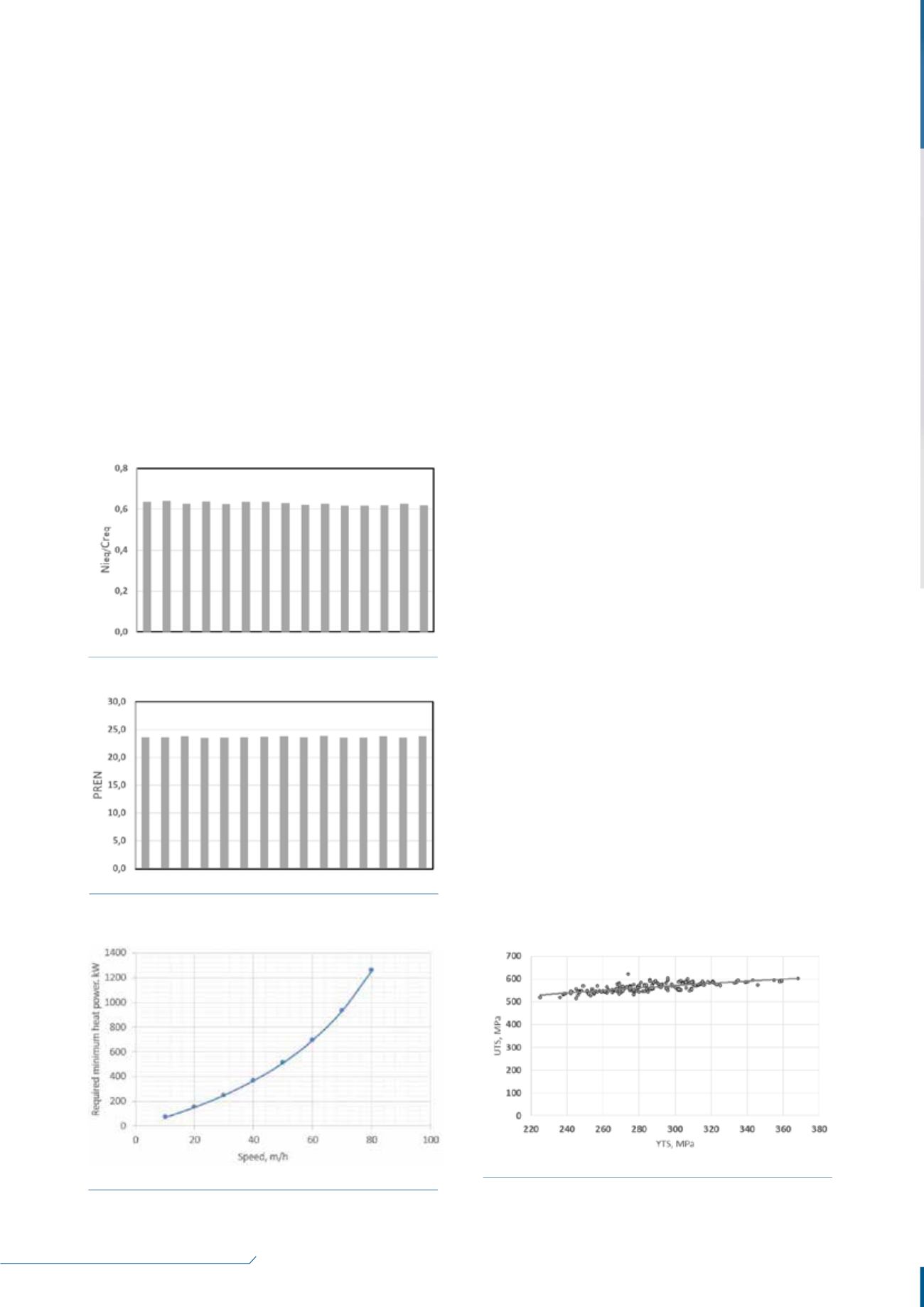

load in the furnace. Transient heat transfer calculations

show that, for continuous furnaces, the required

translation speed of the tubes is proportional to the heat

power, and inversely related to the total area of cross

sections of the load. Figure 5 presents an example of

calculations for a set of tubes, showing the calculated

heat power vs speed of the rollers of the furnace,

demonstrating that the dependency is not linear – faster

speeds require disproportionally higher heat inputs.

Figure 5.

Furnace heating power vs translation speed.

Figure 6.

Ultimate tensile strength (UTS) vs yield tensile

strength (YTS).

Figure 4.

Pitting resistance equivalent numbers (PREN).

Figure 3.

Nickel-to-chromium equivalent ratios.